Following the road of RAFFIA fibre with Asia NYEMBO Mireille :

How can one rewrite history when it has become synonymous with culture and identity and is worn daily ? Stakes are high, however the work of visual artist Asia NYEMBO Mireille who aims at reestablishing the raffia fibre in favour of the wax cloth has broader resonance. In this interview, the Belgium-based Congolese artist highlights history’s unfortunate shortcomings and the imminent duty of restoration

Restoring traditional CONGOLESE culture through ARTS and WORDS.

Is it possible to walk with confidence when the shadow of the past still makes one shudder ? Is it possible to be when one is not at peace with its origins ? How can one rewrite history when it has become synonymous with culture and identity and is worn daily ? Stakes are high, however the work of visual artist Asia NYEMBO Mireille who aims at reestablishing the raffia fibre in favour of the wax cloth has broader resonance. Beyond artistry, the installations and paintings of the Belgium-based Congolese artist highlight history’s unfortunate shortcomings and the imminent duty of memory and soul searching down to each to achieve.

Mayi.Arts : You were born in Kalemie (Congo) where you spent your first years, where does your passion for arts come from ?

Asia NYEMBO Mireille : I started drawing, aged 13. I can precisely remember the first time I handed a pencil to replicate a picture. I remember seeing how precise the final piece was and thinking maybe there was a way to explore there. I used to not speak so drawing became my voice, I thought it interesting to talk through images instead of using words. At that time, my goal was to become a doctor or a biologist something my father was very supportive of and I ended up graduating in biochemistry. I was still drawing but I was not considering going to art school at all.

Facing conflicts and death early

A.N : The conflicts I have witnessed shaped the person that I am today and have had a major impact in my life. My youth has been marked by the separation of my parents but above all by chronic disease which required long periods of isolation in hospital where my only company was that of the nurses. When I was finally able to return to my family home, the Rwandan conflict broke out. I was only ten at the time. We had to move from our hometown and start again in a new town. I quickly became a target, to the point of being arrested, suspected to be a Rwandan. That day, I faced death. They had taken away all the Rwandans, some never come back. When I was sixteen, both of my parents died.

I had a lot on my plate for such a young age. I started using my pencil to externalise all those wounds that were living inside of me. Life conditions in Congo did not improve and it became very tough for me. Going to medical or biology school meant that I had to fund and support myself for seven years. This is when I decided to follow what my inner self was telling me and enrol in the Academy of Fine Arts of Kinshasa

The Academy of Fine Arts of Kinshasa

The artist dwelled into many explorations before finding her way as she recalls : “I first started in interior architecture which I liked. However, it was limiting for self-expression. So I started attending various workshops to explore different styles. The point was really to bring out what was inside of me, not just put it on the outside but also pull myself out, find out how I could solve these problems and go beyond.”

M.A : Identity appears as a reoccurring notion through your work.

A.N : I grasped this notion of identity early in my work even though at that time I couldn’t precisely seize the notion. I was an outcast in Congo as I looked more like a Rwandan or Indian. I knew my mother had Rwandan, Tanzanian and Indian lineage while my father was of Rwandan descents. All of this made me want to question myself. I then started to build my family history from my birth to then go back to the history of my father, the history of my mother then the history of my father's tribe and the history of my mother's tribe. Gradually, starting with my own lineage, I built the history of my country. I was able to trace back then the origins of my attraction to literature and architecture, answers to questions, why I do art and why I am Congolese. And what is the Congo? And what am I ?

During and after her studies in Kinshasa, Nyembo works in interior design and various related fields including in cinema. However and as in any epic tale, comes an event that confronts our hero with the choice of accepting their mission and go headlong into the adventure or refusing it. And if there was a catalytic moment for Asia Nyembo, it would undoubtedly be that 8 March 2009, as she remembers.

A.N : We were celebrating Women's Day and all women had to wear Dutch wax cloth, which I refused to do because of what it represented. I was arrested for not complying. The fact that I raised my voice to defend myself, I understood that there was something wrong. Speaking with one of the policemen who had just arrested me, I explained him the whole history of the wax cloth, its origin. He was stunned as it was the first time he was hearing this. Same for the people around us. I understood at that moment how little of a collective consciousness we had in my own country. We were dressing ourselves without even knowing what we were putting on our skin. After this episode, I decided to dedicate a part of my life to art. An art not for me but to correct certain things that were happening around me and which mainly affected the culture of my country.

Following the road of raffia fibre

Correction over deconstruction, making peace with your own history in order to move forward, this is what Asia Nyembo insists on.

A.N : I always explain my work process starting from its origins. Raffia has an important value because it is through its fibre that I have created my two main materials of work: the dye and the pigment. My precise goal through this work is first to deconstruct culture as we see it today in Congo, in the way of thinking of the Congolese. The goal is not to go after culture as we perceive it today, that is to say from a material point of view, but more from a conceptual and conscious point of view. I have this feeling that my work can at least have an effect in terms of awareness to my fellow Congolese people, to promote the ancestral textile first and then the textile of today which is the result of foreign importation.

”When we go further we realise that several patterns we still wear today in African countries are patterns and motifs retracing the history of the Javanese people (!)”

Asia Nyembo engaged in an in-depth research work around textile. An almost scientific research that she materialised a few years later in 2017 when she joined a residency at TAMAT - Museum of Tapestry and Textile Arts in Tournai (Belgium.)

A.N : When I started my research on raffia fibre, I wanted to trace history through my own past, to know what was before the wax cloth. To answer this question, I had to study history, find out how this textile came to Africa. I found out that the wax was only copies of the Indonesian Batik created in Holland. Indonesians loved inscribing their culture on white cloth using beeswax. When we go further we realise that several patterns we still wear today in African countries are patterns and motifs retracing the history of the Javanese people (!) At the same time, I also discovered a lot of interesting ancestral textiles on which the symbols were not just strange designs, but real messages, incredible libraries of information. It is this wealth that I wanted to promote in favour of the wax loincloth. And to promote this ancestral textile, I looked into its raw material: the raffia fibre.

My mother was from a water kingdom and lived by a lake while my ancestors were sailors and my father’s ancestors were from a fire kingdom. I decided then to immerse and burn the fiber. I collected particles from the water, ashes from the fire.

“What to do with this hard, deep black fabric?”

Looking at those those particles in the water, I had the idea to transform them into a form of dye. I created a mix suitable for raffia fiber, in ocher tones, another yellow. As for the ash, I eventually turned it into a strong, black pigment. Armed with the dye in one hand, the pigment in the other, I was finally ready to express myself. And in those two elements, the history of my country. It was like bringing this ancestral fiber back into the contemporary world.

Déconstruction, Raffia pigments on a wax loincloth, 2017

"Gather and rebuild this fabric because it will never leave Africa". It is now a part of us, deep in our roots, almost a second culture. This is how I have deconstructed to rebuild.

A.N : My first thought was to conceal the meaning of the wax loincloth. The most important thing was to erase those patterns. For two weeks I was haunted by the thought of what to do next, what to do of this cloth that has now become stiff ? From there I decided to explode it in many parts. I used mathematics from Congo, with the Ishango's calculator as a reference [the oldest in the world, more than 25,000 years old.] My ambition was to highlight the intelligence of the Congolese people in this ancestral period. That's how I started to explode the fabric into several little squares, either twelve or four centimetres. The next step appeared as obvious to me, I needed to gather it all together now. I thought "Gather and rebuild this fabric because it will never leave Africa". It is now a part of us, deep in our roots, almost a second culture. This is how I have deconstructed to rebuild.

M.A : Did you anticipate the public reception of such an impactful work ?

A.N : The first time this work was shown for the public, most people were intrigued, faced with something that they had not experienced nor seen yet. It was like being faced with a story displaying a work of art and not the other way round.

To reconcile fragments from the past and be at peace with our contemporary identity.

Ancestor, Raffia ashes and gold on wax loincloth, 2017

“It is time for each of us to take our history in hand, in any field whatsoever, write it where it does not exist, correct it where it goes wrong, rewrite it, where it has been erased, to tell it, to enhance it, and never ever quit. ”

A.N : This sentence is a cry from the heart. It came to my mind after I exploded this cloth. I pronounced last year at an international conference in Washington while I was the only black and African ambassador to represent the African and Congolese culture especially. I said it for the first time in public on that day because I felt it was finally time.

M.A : Indeed, How can one feel when exposing this personal outlook which nevertheless has such a universal resonance?

A.N : When I start talking, my ego gets loose, I am just a human conveying a message. Changing a person, changing a culture is impossible, but you can change thinking. And to change thinking in a culture, it has to start with only one person and if I am that person, I know that another Congolese will be inspired to do so, then another one and one day it will even be a Chinese for example who will find what there is something wrong in their culture and who will not want to damage nor change it, but just to correct it. It is important to know how to move forward while preserving its culture and incorporating other cultures that come from far away because the world cannot only live in its ancestral originalities. We have always had had crossings of culture, crossroads of histories, but how we cross them shapes the future of a people. In Congo, the ancestral past has been forgotten a lot to the point of becoming void and embracing wax for example. However, we cannot be embracing and walking wearing wax and ignoring who we are.

M.A : We are seeing a new world coming in that direction though

A.N : There is higher awareness now. It's still mild but that’s already a good start ! I’d also say the diaspora has a different type of awareness compared to an African born. An African does not realise his hybridisation until he arrives in Europe. It’s a term myself did not use until I got to Europe myself. When you are in your country in the continent, speaking French, going to school, dressing in a certain way is part of everyday life. We do not necessarily realise that we live in a society with two civilisations which coexist at the same time: the ancient African civilisation and the Western European civilisation.

“Inside of me, I have a part of their civilisation. I am the alien still I have a part that ressembles them. And that part precisely, they do not acknowledge it. When they look at me, they think I'm not like them and that's when I realise there is something wrong.”

This is where us living in the West, far away, start this quest, looking in the past, to find out where did the rupture took place, and how to recover what was there before that we lost. Rearrange even a little bit things.

M.A : Do we cure from this wound ?

A.N : We have to build the new, and if everyone realises this, together we will build something huge and strong. I think that to this day, Westerners know that if Africans people manage to realise their hybridisation and really create bridges with their history, they will go beyond the limits of their civilisation and reach new heights. We still have a lot of hidden things within our civilisations: in messages, in symbols, in the tales of our ancestors. If we find each of these fragments and revisit them today, especially with our technologies, we are going to discover incredible things that will move Africa forward.

Positive outlook on the future

A.N : My advice to each is to reconnect with yourself. When we refuse to connect with ourselves, we seek to and refer to and from someone else. You have to go look at your history first. If in my ancestral history there were, for example, textiles with incredible techniques, why can't I start by learning these techniques and reworking them with today's means? Why start by learning the techniques of the West? In these techniques, you will find their history, their culture that made what they are today. Why not go looking within your origins to define yourself ?

In politics for example, despite many years, we still cannot find the solution in the country. This is because we have an operating model based on Western civilisation. However, there is within us an ancestral political foundation that we have abandoned, which is within our blood, in our behaviour and in our way of life. It creates two different flows that are in conflict inside and outside of us. We have to go back to find out how ancestral societies functioned and understand how we function in order to be able to add then democracy that is of Western construct to improve the well-being in our country.

A person who loves to talk for example, all he has to do is go at his grandparents, look for all these beautiful stories that existed in which we find fragments of information, education, morals, manners and know-how. Go find these tales there, rework them and tell them again, to push the oratory art. Writing, letters is a tradition closely tied to the West, why not promoting ours ?

Artist and Woman

Identity is a running theme through the work of the multi-skilled artist. Asia Nyembo navigates through her multiple identities and never stops questioning the origins of preconceptions, especially when it comes to her identity as a woman in arts.

A.N : I have explored women through different works, all women, not just African women. As women, we sometimes have a hard time realising our power yet we have so much potential within us. Each woman has the ability within her to make change in this world, in her continent, her country or her family or simply within her and this in various directions. If men have taken the power to dominate women over time and put her aside, it is partly because men are aware of this potential. A great part of ancient civilisations in Africa or elsewhere have valued women by adopting matriarchal cultures at the point in history. The question is should we wait for men to realise this again or is it not up to us women to realise it and go revive that personal potential we have ? I often represent this hidden power of women in my work. This hidden power within us that we just have to look for. If we look for it, we end up finding it, and when we do find it, we become strong human beings.

M.A : Even more so as a woman and an artist.

A.N : A woman who is an artist is a woman who if she is not strong, will stop halfway because it is a world of fights. You have to assert yourself every moment for your work to be accepted. For example in my country and in other cultures it is still delicate. Women often give up and fast. From an outward look, some take the bets and predict that it will take a marriage or a child to come for all the art to end up in the kitchen. Something I have heard many times. It’s only when a woman keep going and creating despite these life events and only there that she will be recognised as a strong woman by her fellow artists.

The thing is a woman is strong in what she is, from the beginning. She is the one choosing this path and who will have to fight against all these comments coming from the mouth of men. I put the emphasis on the ability to have a great inner strength ready to fight against anything negative that will come from the outside, anything that will come to destroy the artist who is inside. If we can get past this, be strong from within, we will succeed. Being a woman and an artist is a long fight.

M.A : Did you really on this inner strength during the past months ?

AN : The past months have disrupted many aspects of my work. Everything stopped for a moment. I lost exhibitions, the Dakar Biennale was postponed [...]

We [the artists] have lost a lot of the moments and opportunities and this has impacted our work. From a psychological point of view too. I had to call on my inner strength. To hold out, I transformed this period into a personal residence, which allowed me to create new works and to pursue my work and historical research. We adapt. We take the time to create new projects, to write them, to put them in place before finding again seeming normality.

Asia Nyembo Mireille recently partook in AKAA Fair and is also programmed at the next Dakar Biennale.

In conversation with Nobukho NQABA

Nobukho Nqaba tells her story about migration and being a foreigner in South Africa using China mesh bags and daring performances

We met with South African visual artist and performer Nobukho Nqaba. We discuss work, education and views on migration and what it means to be a foreigner even to your own country.

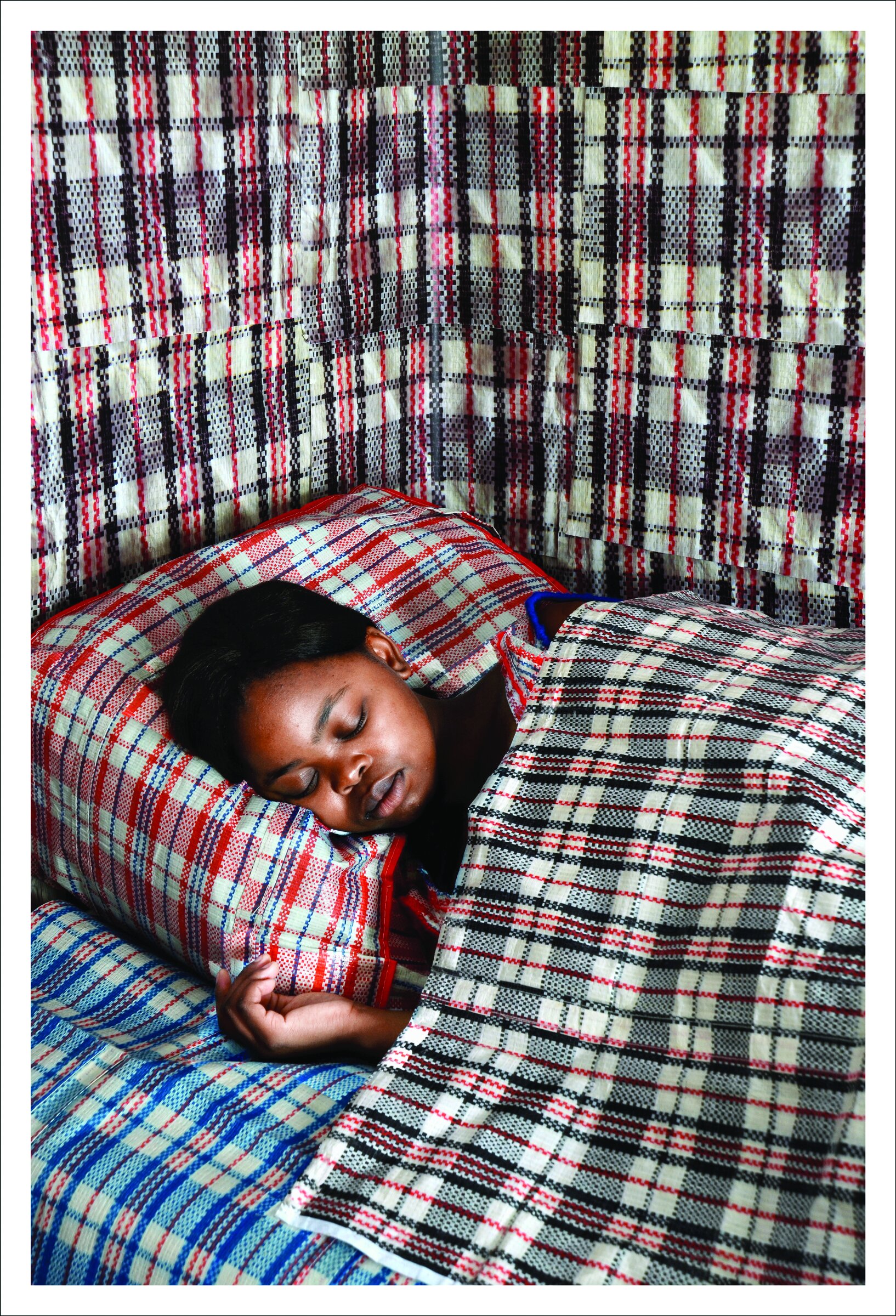

Nobukho NQABA, Ndiyayekelela

Mayi.Arts : How do you define your work ?

Nobukho NQABA : I would say my work is performative, but uses elements of self portraiture while addressing personal and broader issues of people who come from or are from marginalised communities in South Africa, more especially the working class.

M.A : One of our first focus stories is about migration, what does this evokes you ?

N.N : Migration is broadly understood as movement of people, themes of displacement, searching and looking for something better comes to my mind when I think about migration. While others choose to migrate and they have the means to do so, other people are forced to do so because of war, poverty , etc. One thing that we can all understand when it comes to migration is that one identifies a lack of something, and they set about finding ways to address that lack or need by moving to spaces that are potentially going to give them a “better” life.

M.A : Self portrait is prevalent mean of expression in your work, which is a very intimate form of portraying : you and a camera. How did you start being involved in photography ?

N.N : I studied photography at the Michaelis School of Fine Art (University of Cape Town). I had never been in a darkroom before or processed images using chemicals. My family does not even have photographs of us when we were young. I was so drawn into the medium , both from a curious point of view, but also for making sure that I make my presence felt by using an analogue or digital footprint of my face. Almost making up for lost time.

People respond to different visual forms, a photograph evokes a strong permanent stance, one that will last forever and can be reproduced.

Nobukho NQABA

M.A : ... But you also do performances, in which you are object and subject through the eye of people and the way they interact with you,

N.N : When I perform, I am extending from the stillness of the photograph. I want to bring what is frozen to life. People respond to different visual forms, a photograph evokes a strong permanent stance, one that will last forever and can be reproduced. While a performance is often a moment in time that is unfrozen, it is restless, moves and often evokes something from the subconscious mind. Although using the body, it is abstract in a way, it is driven by feeling and movement. I think both photography and performance complement each other, because each borrows from one another.

M.A : We are referring here to your performance in front of V&A waterfront as part of Ndiyayekelela. A striking element was the different reactions of people. How comfortable were you during this performance ?

N.N : I am always nervous when I start performing, because one never knows what kind of a reaction they will get from the audience. It was the same case for the said performance, however, I had a message that I wanted to bring across, and I wanted people to see it. What kept me going was to switch of mentally and not think of the people around me, but focus on what I was doing, as if it was just me and my objects in space.

M.A : Is this a parallel of how society behaves towards the working class which is dominant but at the same time invisible ?

N.N : Probably yes, the working class footprint is everywhere in the city, but they are often overlooked, as if they do not matter. A lot of people just do not stop to think about, the labour that they do, nor their experiences, or the fact that a lot of them build beautiful architectural structures , but they themselves live in shanty towns where they do not have enough space, and are unable to build for themselves because they earn so little. Or that domestic workers leave their children to go to work in the early hours of the day, taking care of other people’s children while theirs are left alone. Often the eldest being the one who has to take care of other siblings, leaving a broken family structure, where the parents come home late…after having left early, and there's no reflection on the day's work. The cycle carries on, and this results in dysfunctional families. The examples are endless...

“ With that particular performance, people stopped and stared, others asked questions and others just simply carried on with their shopping. Other people asked if they could bring their own laundry for me to do. ”

M.A : What were the intents behind this performance and the whole series ? Did people actually interacted with you ?

N.N : The performance was in two parts. The first part was when I walked around the V&A waterfront wearing the China bag, and standing at a frame that shows Table Mountain (an area where lots of people take pictures/ selfies). I received some unpleasant responses from some people, this includes being called a thing. And I recall a tourist who wanted me to move so that they can have their picture taken, said to me “she is fucking African, she cant understand English”. A woman also physically touched me on my chest telling me of how selfish I was for standing at the table mountain frame longer.

The second part was when I washed the overalls in front of the shop, and hung them on a washing line. With that particular performance, people stopped and stared, others asked questions and others just simply carried on with their shopping. Other people asked if they could bring their own laundry for me to do.

The performances were for me to ask Cape Town, especially the waterfront to recognise that hard labour from the working class made it what it is. I wanted to make the working class visible. I also wanted to highlight the fact that those who enjoy the luxurious waterfront are often people who are not from South Africa, hence I was wearing the china bag in the first part. That they are themselves foreign to the space, however the space is also foreign even to those who take care of it. The V&A waterfront is such a weird space for me to be in. It’s one of the areas that i feel very much removed from, that it is in my country, but yet it is also not built for a person with my background, except for a tiny section there, where you will find affordable food shops. It is a space that is screaming of social stratification in terms of class, and affordability.

M.A : In the past you discussed the notion of being a foreigner occurrences in which you have been called such and even a kaffir this the fate of each who migrates ? To be a forever nomad ?

N.N : Yeah... the term foreigner in my context is often used to refer to someone who was not born in the country they are in. A lot of people in South Africa refer to other people who come from other countries as foreigners. This is a negative word, because it discriminates against fellow African people. Being foreign is associated with certain stereotypes, how one speaks and how one looks. I was called a foreigner once by a group of men, who were cat calling me on my way from work. Because I did not reply to their advances, they decided to insult me, and I remember one of them saying “Can’t you see she is a foreigner”, she cant even hear us.

Which also makes me think of when I was in art school, and one of the car guards on the street across campus, always told me that I am Congolese. He was certain that I am from Congo, because I looked a certain way and he kept saying he saw me somewhere. It did not help telling him that I do not understand French, and that I can only speak English and in Xhosa. He thought I was ashamed of being a “foreigner”.

Often being originally from the Eastern Cape , and residing in Cape Town, in times of tensions Eastern Cape people are sometimes told to go back to the rural areas. This is further fuelled by some politicians, one in particular called people from the Eastern Cape who reside in Cape Town “refugees”.

The word Kaffir was was used by the Apartheid government to refer to black South Africans. It is now a banned word to use in South Africa, however, some racist white South Africans still use it to speak down on black south africans or to make them feel inferior. Yes, I was called that word and it made me angry because that word is discriminatory.

These experiences made me think really hard about what it means to be an ‘other’ or to be considered foreign. There are so many layers to unpack, which obviously include certain stereotypes, which are harmful.

M.A : As it is also part of your personal story ...

Yes, from a personal level and from a professional practice, especially the work that I did in 2012 (Umaskhenkethe Likhaya lam), I looked at migration within one's own country of birth. In my case (family), moving from the Eastern Cape to the Western Cape, and the experiences that come with that. I mostly focus on objects, memory and symbolism to make work about my personal experiences.

M.A : Which brings us to Umaskhenkethe, as a reference, those bags didn’t really have a name in some countries, in France for example, they’d be referred to as ‘Tati Bags’ [name of the store where a lots were sold ]and commonly ‘Barbès Bags’ [Barbès used to be the multicultural district of Paris ] , they had a really negative perception. aCarrying those bags because meant fresh out of your country and not integrated yet but also poor.

Was it important for you to rewrite the story of these bags and their narratives as they are part of the most African households ?

N.N : it is interesting that in France those bags are associated with a space that is full of migrants. This speaks volumes about how this bag is a global symbol of migration, and at least from a migrant perspective as a symbol for the working class and of those who belong in a certain social stratum in society.

For me it is important to take these objects and symbols and make them visible. I am taking the “in your face” kind of approach, that these objects, practically and symbolically need to be seen, doing so to make the people who use them visible. Symbolically elevating them from being overlooked.

M.A : Watching this series we can see the mesh bags being used as a bag, a pillow, wallpaper, what was the starting point of this extensive work ? What was the process ?

N.N : I started off by having conversations with people in Cape Town about their associations with the bags. I got a lot of interesting stories, and I then dug deep into what I was so drawn into this back, and I realised how similar my story was to that of the people I had interviewed. It was a difficult and long process, one which required listening, contemplating and making a visual output.

Working with the material was challenging, because it is hard plastic, and does not fold like a normal fabric. I have had to cut the bags up, flatten them so that they can at least have some sort of flexibility, and I had to improvise in some areas, where I used colour scans of the bag, printed them on paper and used them.

M.A : In the past you mentioned observing people as a source of inspiration, what else inspires you ?

I am still inspired by people, and how they interact with one another. I am also inspired by fellow artists who are investigating, deconstructing and exploring similar themes as me.

M.A : Would you define yourself as an activist ? Is it important for you to guide people in their interpretation of your

work ?

I do hope that the work that I do makes people think beyond, about society’s issues. I really hope that one day things will change and be better for most. I am an activist? I do not know, it depends on how one understands that word. What I do know is I am making work about issues that are close to my heart, and issues that matter.

I always say that my work provides a framework of broader societal issues, however it is not a deciding factor. People must look at it , and insert their own selves in the issues that I address. I am not guiding them, but I am simply asking them to look around what's happening, and that something needs to change in the way that we deal with each other.

M.A : When did you decide to become an artist? Was this your first calling, can you tell us about your path ?

N.N : Probably since high school. I always wanted to be either a social worker or an artist. but i realised that I feel much more at peace when I express myself creatively.

M.A : Tell us more about being a woman artist in South Africa, what is the scene these days

N.N : Things are slowly moving, we have seen a few female artists being visible and exhibiting. But there is still a long way, the art scene is still very male dominated. Female artists are pushing, and they are not waiting on establishments to discover them, they form their own collectives and encourage each other, and that is a beautiful thing. There is a strong sense of empowerment, and care that we give each other as females.

M.A : You lecture as well...

N.N : Yes, I lecture photography at one of the tertiary institutions in Cape Town. It has been a year now, and I am really enjoying it. Prior to that I was teaching Visual Arts, and digital photography for five years at one of the local art centres in Cape Town. I have always been doing some teaching while being a practicing artist at the same time. I believe in the power of art education, and teaching is one of the things that I enjoy. and I think for me both being an artist and a teacher is paramount, none overtakes the other. I believe that I am teaching people through my art, and I have a duty to educate the next generation of artists as well, hence i do both.

M.A : What is your favourite artwork of yours ?

I don't really know which one... (laughs) ! Some days I like a particular work, and other days I do not like it that much. I am constantly thinking of ways to make the best work, and thinking

M.A : Any upcoming work, work in progress ? How do you keep your peace as covid-19 has changed many aspects of our lives ?

N.N : I have been using this time to teach, and to reflect on what is happening around the world. I have not committed to making new work, it takes me a long time to make work. i spend a lot of time just thinking things through, and when i feel that the time is right, then i produce.

M.A : Where do you feel home now ?

N.N : For me home is where I am with people I love. I am in a good space with my family, and I think that is just good enough for me.

Interview by Mayi-Arts. All pictures are courtesy of Nobukho Nqaba