In conversation with Nobukho NQABA

We met with South African visual artist and performer Nobukho Nqaba. We discuss work, education and views on migration and what it means to be a foreigner even to your own country.

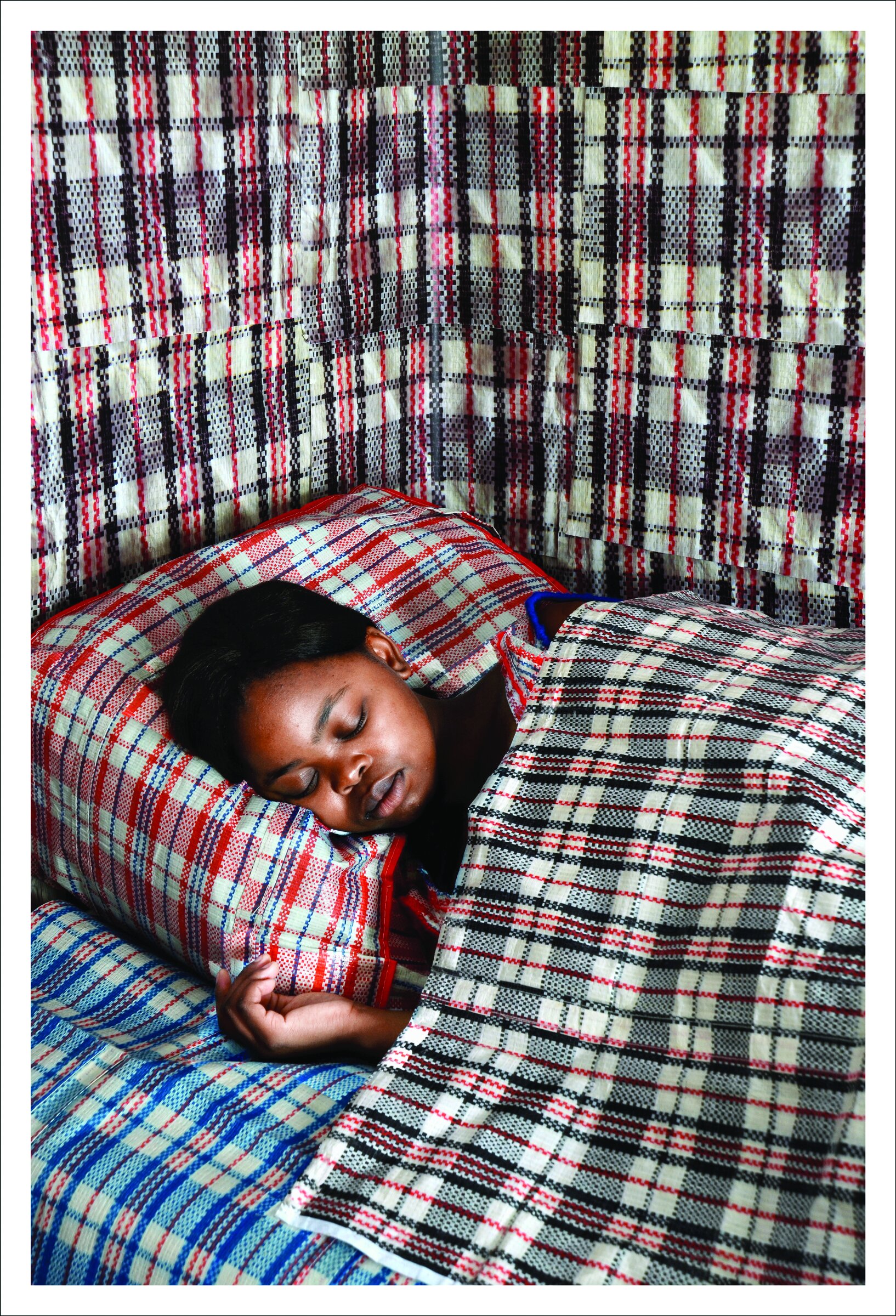

Nobukho NQABA, Ndiyayekelela

Mayi.Arts : How do you define your work ?

Nobukho NQABA : I would say my work is performative, but uses elements of self portraiture while addressing personal and broader issues of people who come from or are from marginalised communities in South Africa, more especially the working class.

M.A : One of our first focus stories is about migration, what does this evokes you ?

N.N : Migration is broadly understood as movement of people, themes of displacement, searching and looking for something better comes to my mind when I think about migration. While others choose to migrate and they have the means to do so, other people are forced to do so because of war, poverty , etc. One thing that we can all understand when it comes to migration is that one identifies a lack of something, and they set about finding ways to address that lack or need by moving to spaces that are potentially going to give them a “better” life.

M.A : Self portrait is prevalent mean of expression in your work, which is a very intimate form of portraying : you and a camera. How did you start being involved in photography ?

N.N : I studied photography at the Michaelis School of Fine Art (University of Cape Town). I had never been in a darkroom before or processed images using chemicals. My family does not even have photographs of us when we were young. I was so drawn into the medium , both from a curious point of view, but also for making sure that I make my presence felt by using an analogue or digital footprint of my face. Almost making up for lost time.

People respond to different visual forms, a photograph evokes a strong permanent stance, one that will last forever and can be reproduced.

Nobukho NQABA

M.A : ... But you also do performances, in which you are object and subject through the eye of people and the way they interact with you,

N.N : When I perform, I am extending from the stillness of the photograph. I want to bring what is frozen to life. People respond to different visual forms, a photograph evokes a strong permanent stance, one that will last forever and can be reproduced. While a performance is often a moment in time that is unfrozen, it is restless, moves and often evokes something from the subconscious mind. Although using the body, it is abstract in a way, it is driven by feeling and movement. I think both photography and performance complement each other, because each borrows from one another.

M.A : We are referring here to your performance in front of V&A waterfront as part of Ndiyayekelela. A striking element was the different reactions of people. How comfortable were you during this performance ?

N.N : I am always nervous when I start performing, because one never knows what kind of a reaction they will get from the audience. It was the same case for the said performance, however, I had a message that I wanted to bring across, and I wanted people to see it. What kept me going was to switch of mentally and not think of the people around me, but focus on what I was doing, as if it was just me and my objects in space.

M.A : Is this a parallel of how society behaves towards the working class which is dominant but at the same time invisible ?

N.N : Probably yes, the working class footprint is everywhere in the city, but they are often overlooked, as if they do not matter. A lot of people just do not stop to think about, the labour that they do, nor their experiences, or the fact that a lot of them build beautiful architectural structures , but they themselves live in shanty towns where they do not have enough space, and are unable to build for themselves because they earn so little. Or that domestic workers leave their children to go to work in the early hours of the day, taking care of other people’s children while theirs are left alone. Often the eldest being the one who has to take care of other siblings, leaving a broken family structure, where the parents come home late…after having left early, and there's no reflection on the day's work. The cycle carries on, and this results in dysfunctional families. The examples are endless...

“ With that particular performance, people stopped and stared, others asked questions and others just simply carried on with their shopping. Other people asked if they could bring their own laundry for me to do. ”

M.A : What were the intents behind this performance and the whole series ? Did people actually interacted with you ?

N.N : The performance was in two parts. The first part was when I walked around the V&A waterfront wearing the China bag, and standing at a frame that shows Table Mountain (an area where lots of people take pictures/ selfies). I received some unpleasant responses from some people, this includes being called a thing. And I recall a tourist who wanted me to move so that they can have their picture taken, said to me “she is fucking African, she cant understand English”. A woman also physically touched me on my chest telling me of how selfish I was for standing at the table mountain frame longer.

The second part was when I washed the overalls in front of the shop, and hung them on a washing line. With that particular performance, people stopped and stared, others asked questions and others just simply carried on with their shopping. Other people asked if they could bring their own laundry for me to do.

The performances were for me to ask Cape Town, especially the waterfront to recognise that hard labour from the working class made it what it is. I wanted to make the working class visible. I also wanted to highlight the fact that those who enjoy the luxurious waterfront are often people who are not from South Africa, hence I was wearing the china bag in the first part. That they are themselves foreign to the space, however the space is also foreign even to those who take care of it. The V&A waterfront is such a weird space for me to be in. It’s one of the areas that i feel very much removed from, that it is in my country, but yet it is also not built for a person with my background, except for a tiny section there, where you will find affordable food shops. It is a space that is screaming of social stratification in terms of class, and affordability.

M.A : In the past you discussed the notion of being a foreigner occurrences in which you have been called such and even a kaffir this the fate of each who migrates ? To be a forever nomad ?

N.N : Yeah... the term foreigner in my context is often used to refer to someone who was not born in the country they are in. A lot of people in South Africa refer to other people who come from other countries as foreigners. This is a negative word, because it discriminates against fellow African people. Being foreign is associated with certain stereotypes, how one speaks and how one looks. I was called a foreigner once by a group of men, who were cat calling me on my way from work. Because I did not reply to their advances, they decided to insult me, and I remember one of them saying “Can’t you see she is a foreigner”, she cant even hear us.

Which also makes me think of when I was in art school, and one of the car guards on the street across campus, always told me that I am Congolese. He was certain that I am from Congo, because I looked a certain way and he kept saying he saw me somewhere. It did not help telling him that I do not understand French, and that I can only speak English and in Xhosa. He thought I was ashamed of being a “foreigner”.

Often being originally from the Eastern Cape , and residing in Cape Town, in times of tensions Eastern Cape people are sometimes told to go back to the rural areas. This is further fuelled by some politicians, one in particular called people from the Eastern Cape who reside in Cape Town “refugees”.

The word Kaffir was was used by the Apartheid government to refer to black South Africans. It is now a banned word to use in South Africa, however, some racist white South Africans still use it to speak down on black south africans or to make them feel inferior. Yes, I was called that word and it made me angry because that word is discriminatory.

These experiences made me think really hard about what it means to be an ‘other’ or to be considered foreign. There are so many layers to unpack, which obviously include certain stereotypes, which are harmful.

M.A : As it is also part of your personal story ...

Yes, from a personal level and from a professional practice, especially the work that I did in 2012 (Umaskhenkethe Likhaya lam), I looked at migration within one's own country of birth. In my case (family), moving from the Eastern Cape to the Western Cape, and the experiences that come with that. I mostly focus on objects, memory and symbolism to make work about my personal experiences.

M.A : Which brings us to Umaskhenkethe, as a reference, those bags didn’t really have a name in some countries, in France for example, they’d be referred to as ‘Tati Bags’ [name of the store where a lots were sold ]and commonly ‘Barbès Bags’ [Barbès used to be the multicultural district of Paris ] , they had a really negative perception. aCarrying those bags because meant fresh out of your country and not integrated yet but also poor.

Was it important for you to rewrite the story of these bags and their narratives as they are part of the most African households ?

N.N : it is interesting that in France those bags are associated with a space that is full of migrants. This speaks volumes about how this bag is a global symbol of migration, and at least from a migrant perspective as a symbol for the working class and of those who belong in a certain social stratum in society.

For me it is important to take these objects and symbols and make them visible. I am taking the “in your face” kind of approach, that these objects, practically and symbolically need to be seen, doing so to make the people who use them visible. Symbolically elevating them from being overlooked.

M.A : Watching this series we can see the mesh bags being used as a bag, a pillow, wallpaper, what was the starting point of this extensive work ? What was the process ?

N.N : I started off by having conversations with people in Cape Town about their associations with the bags. I got a lot of interesting stories, and I then dug deep into what I was so drawn into this back, and I realised how similar my story was to that of the people I had interviewed. It was a difficult and long process, one which required listening, contemplating and making a visual output.

Working with the material was challenging, because it is hard plastic, and does not fold like a normal fabric. I have had to cut the bags up, flatten them so that they can at least have some sort of flexibility, and I had to improvise in some areas, where I used colour scans of the bag, printed them on paper and used them.

M.A : In the past you mentioned observing people as a source of inspiration, what else inspires you ?

I am still inspired by people, and how they interact with one another. I am also inspired by fellow artists who are investigating, deconstructing and exploring similar themes as me.

M.A : Would you define yourself as an activist ? Is it important for you to guide people in their interpretation of your

work ?

I do hope that the work that I do makes people think beyond, about society’s issues. I really hope that one day things will change and be better for most. I am an activist? I do not know, it depends on how one understands that word. What I do know is I am making work about issues that are close to my heart, and issues that matter.

I always say that my work provides a framework of broader societal issues, however it is not a deciding factor. People must look at it , and insert their own selves in the issues that I address. I am not guiding them, but I am simply asking them to look around what's happening, and that something needs to change in the way that we deal with each other.

M.A : When did you decide to become an artist? Was this your first calling, can you tell us about your path ?

N.N : Probably since high school. I always wanted to be either a social worker or an artist. but i realised that I feel much more at peace when I express myself creatively.

M.A : Tell us more about being a woman artist in South Africa, what is the scene these days

N.N : Things are slowly moving, we have seen a few female artists being visible and exhibiting. But there is still a long way, the art scene is still very male dominated. Female artists are pushing, and they are not waiting on establishments to discover them, they form their own collectives and encourage each other, and that is a beautiful thing. There is a strong sense of empowerment, and care that we give each other as females.

M.A : You lecture as well...

N.N : Yes, I lecture photography at one of the tertiary institutions in Cape Town. It has been a year now, and I am really enjoying it. Prior to that I was teaching Visual Arts, and digital photography for five years at one of the local art centres in Cape Town. I have always been doing some teaching while being a practicing artist at the same time. I believe in the power of art education, and teaching is one of the things that I enjoy. and I think for me both being an artist and a teacher is paramount, none overtakes the other. I believe that I am teaching people through my art, and I have a duty to educate the next generation of artists as well, hence i do both.

M.A : What is your favourite artwork of yours ?

I don't really know which one... (laughs) ! Some days I like a particular work, and other days I do not like it that much. I am constantly thinking of ways to make the best work, and thinking

M.A : Any upcoming work, work in progress ? How do you keep your peace as covid-19 has changed many aspects of our lives ?

N.N : I have been using this time to teach, and to reflect on what is happening around the world. I have not committed to making new work, it takes me a long time to make work. i spend a lot of time just thinking things through, and when i feel that the time is right, then i produce.

M.A : Where do you feel home now ?

N.N : For me home is where I am with people I love. I am in a good space with my family, and I think that is just good enough for me.

Interview by Mayi-Arts. All pictures are courtesy of Nobukho Nqaba